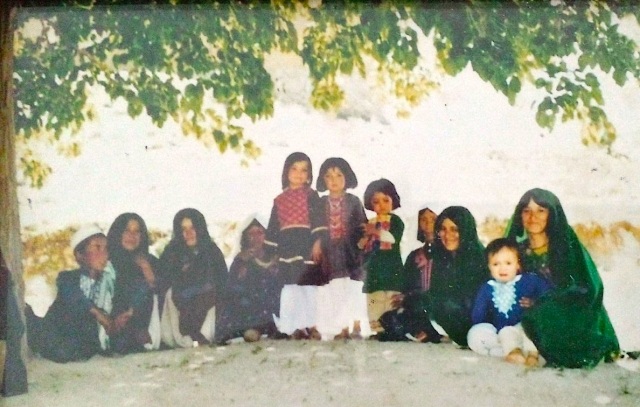

This is from when I was young and strong, and I could work like many men can not. Your father was only a kid, and your aunties were younger. We had had to lease out the family land to repay your grandfather’s debts, and he had a lot of it. Your grandfather fell very ill that year, and had to remain home-bound.

Khalifa offered us some work on his land in the gorge during the summer months. We had to cut the tall grass, prepare the land, and cultivate grain. It was hard work. We worked there as a family, starting at dawn and finishing when darkness made it impossible to see what we were doing. We went hungry every other day and had no spare food.

One day, in the midst of work and the summer, I collapse at work. When I opened my eyes Qareedar’s son, Yaqoob, stood there with some bread in hand. He offered me a piece of it with some milk. I sat upright, ate it as fast as I could, and felt instantly better. I ate some more, and I could get up and return to work again.

We worked there for many weeks, and finally harvested Khalifa’s wheat crop. When it was all thrashed and ready to be loaded on the back on the back of donkeys, he arrived there to weight it. He first claimed his half, and left the other half on one side. We thought that was our share. He then took our half and divided it into smaller portions, claiming those in exchange for what he had provided us with: a portion for the seeds, another for the bull and the thrasher loaned to us for a few days, and another for allowing us to use his farm equipment. He took everything, all of it, not one portion left for us. God curse me if I lie. Nothing for us. He took it all. Allaywar arrived there later in the day, loaded the harvest on the back of a few donkeys to take the wheat to the crusher.

The children stood by me and watched, as I wept in despair. Khalifa’s wife saw this. She was scared of her husband, and could not say anything. She walked over, and discreetly poured a handful of grain into a corner of my skirt and chador. She told me to take it and walk away as fast I could. I did.

I felt as if she had poured the world into my chador. That wheat only fed us for two days and two nights. A summer of hard work, and it was all over in two days.

Curse poverty. When you are poor, people treat you like cattle. Those are the kind of days we had to live through. When you have money, your friends remain friends, your relatives remain close. When you have no money, your own eyes will disown you. Khalifa was a close relative of your grandfather. He had been like family. He did not spare our starving family a plate of the harvest we had worked on.

That is what the world has taught me.