Hassan was nineteen or twenty or perhaps younger, perhaps a little older when he died. I do not recall how and I do not know why. He just fell ill suddenly, and died half a day later.

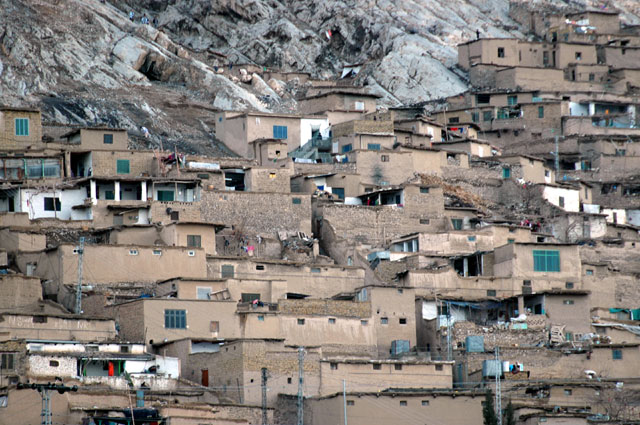

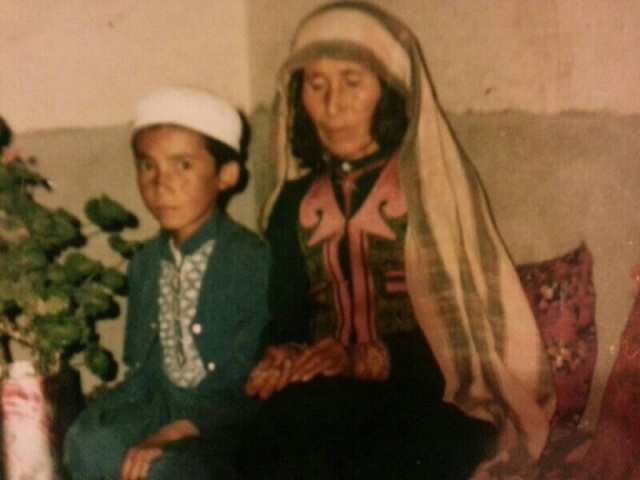

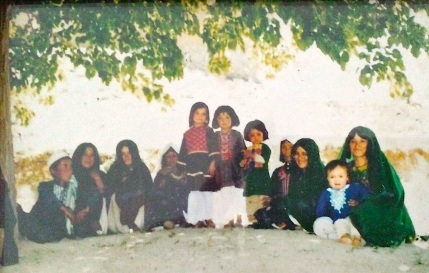

Hassan was my my uncle’s – my father had a half-brother – son. His father and my father were from the same father but different mothers. We were Hassan’s family. He was still a child when he lost his father and mother. He was a clever child, and grew up to become a brave young man. He had learned the spell used to catch snakes and lizards. He would go into the hills and chase snakes when he had nothing else to do. He read the spells, caught snakes, sewed their mouths shut, wrapped them around his neck or waist, and return to the village to scare children and adults alike. He caught big snakes, some so big that it must have been an effort to carry them down the mountains.

I remember this one time when he was bitten by a snake he had brought to the village. We worried and begged him to go and see someone, the mullah perhaps but he was not worried. He murmured his spells a few times and blew it out over the bite mark, and walked back in to the fields. We all thought he was going to die. He returned home, ate and went to sleep. Early the next morning, the old Karblaye came looking for him:

Go and wake him up. Check if he still lives.

No sooner had Karblaye asked for him that Hassan walked out of the room with a smile on his face. He sounded unfazed:

Snakes? No snakes can kill me.

Hassan got married a few years later. He had a daughter. He was a happy person, and adored his baby daughter. He returned from the fields one afternoon and said he was ill. He went to sleep, and just like that, he died. He did not wake up from the afternoon sleep.

I do not know what it was. Perhaps he had been bitten, or perhaps he had an illness. He might have had any of the many diseases that were common in the mountains. There were no doctors and there was no medicine. He died.