Khadim’s father, Hussain’s father and Bachay Atay Jan Ali of SarMazar were the last people to see him alive. They had journeyed together, and then they returned home to their families. He didn’t.

We lost him. We had no one to send to look for him. My oldest boy was 13, my youngest boy was a baby, and in that God-forsaken country, girls cannot travel by themselves. We sat by as months and years passed by. We kept hearing stories:

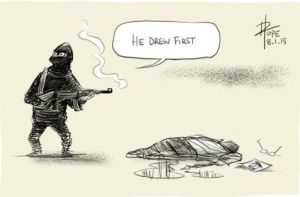

We walked for many days and nights. The days were extremely hot and the nights were extremely cold. And then it began raining such that the Sun and heat disappeared. It kept raining, and it got really cold. The desert was vast, open and had nowhere for us to hide. We were stranded without adequate food and shelter. Khalifa’s son had set off with only the clothes he had on. He had no other clothes to keep him warm. He felt weak, laid under a small tent we made for him using our jackets, scarfs and coats. He shivered, and died of cold in the middle of nowhere.

While the rest of us stopped and talked about returning, he was determined to keep going. He left us there, and walked into the rain and mist. We saw him walk away and disappear in the rain and mist of the desert.

For a long time that was all we knew, and nothing more. Then one day few years later, from the front window of the house, I saw a stranger walk into the village. He paused just past the pass, looked around, and headed straight to our house. He sat outside and said nothing. I felt nervous and sent for your father.

Your father greeted the man:

Salam. You haven’t introduced yourself. What brings you to our home?

He went straight to the point:

I have a letter from your father. I have been sitting here for a long time, and I haven’t even been offered tea.

I and your father just stood there, staring at this man, in utter silence.

Why didn’t you say something?

He looked around. He sounded nervous.

Let’s not talk about it here. Let’s go in and we can talk about it.

We went inside. I made him tea. There was hope after all.

Your father told me the name of your village. He told me to look for a large mulberry tree, and go to the house right next to it. I spotted the tree and your house from the pass. I knew it was the right house.

He asked for a hookah. I sent Zia Gul to my brother’s house to get a hookah. The poor girl was so jubilant, she ran up and told every one about the man. She returned with a hookah, and followed by Hussain’s father.

The man was startled:

Who is he? Why is he here?

I was surprised to see the man that nervous and startled. I tried to calm him down:

He is my brother. He is our own.

Hussain’s father greeted the man. They had tea. He described the journey.

It was cold and rainy in the desert. We were set upon by local bandits. We ran for our lives, and soon became lost. There was more rain, and it became unbearably cold. My brother-in-law wore a shawl. We huddled together and he covered us with his shawl. He lit a cigarette, and took a long puff. He passed it around. It did nothing. There were no more cigarettes left. Khalifa’s son was fragile. He could barely walk. My brother-in-law said we better leave or we would all die. The dying kid didn’t want us to leave. He pleaded with us, and said we would all die anyways. Let’s die together here rather than one at a time. My brother-in-law left the shawl cover, he fastened his belt and shoes, and began walking into the mist. We sat there, huddled together, staring at him walk into the mist.

The stranger raised his hand.

I believe you. He does not know that you all live.

He took a folded paper out of his pocket, stared at it and then put it back.

This isn’t the letter from your father. This is for a family in Kosha.

He searched his other pockets.

I may have left the letter with the other person in Angori.

He instructed your dad to visit Angori, and get the letter from him.

At this moment, my older brother Shaikh walked in.

The man was so started, he almost got up to leave.

Who invited all these people!? Why are you bringing in all these people!?

I tried to calm him again.

He is my brother. He sent you the hookah.

The man did not calm down. He was visibly startled. He slammed the tea container on the ground, got up and headed for the door. My brother followed him. We pleaded with him to tell us more. I begged him to take a letter with him. The man did not wait. He put on his shoes, and headed for the pass.

He took a few steps, and then turned to me.

What kind of brothers are they! Tell them to man up, and go to Iran to find your husband. Your brothers don’t believe me. They ask asking me for the color of his clothes. I take hundreds of people to Iran. How can I remember every person’s clothes and face. Your husband is in Iran. He is fine and healthy.

With those words, he headed for the pass. In the same way that he had walked in, he walked out of the village. He was a people smuggler. He was fearful the villagers would report him to the government. In those days, people smugglers were luring people, and taking their money to take them to Iran. There were rumors that some villages had reported and handed over people-smugglers to the government.

Your father visited the address in Angori. The man there denied any knowledge of the other person, or of your grandfather. He denied he was a people smuggler.

That was that. We never heard from that person again. We looked for him, but no one knew him, or his whereabouts. He disappeared, and so did all our hopes.

Many years later I realized that your grandfather may really have reached Iran. He may have been alive. He was a clan elder and man of honor. He probably thought that he had left behind his brothers in law and friends. He thought they were dead. He probably thought there was no honor in returning to the village without them. To make it worse, the smuggler never returned to return to take a reply letter from us to your grandfather. Perhaps, perhaps that made him think that we didn’t want him back. He probably thought we had given up on him.

It doesn’t matter thought. What difference does it make now. We never heard from him again. We had no way of finding out about him or looking for him. Just like that, he was gone. We still don’t know what happened to him.